Similarity search and Deduplication at scale

With the increase in the application of large-scale data collection, analytics, and accompanying big data platforms over the past decade, the necessity for reliable entity matching solutions is proportionately growing. The newly available data volumes need to be integrated, processed and made usable before further value can be generated.

The fundamental problem of entity matching (also known as record linkage, data linkage, reference reconciliation, data matching, entity resolution just to name a few) lies at the core of many commercial and enterprise applications such as:

- Deduplication

- Similarity search

- Data integration (merging of different data sources)

which cover many different domains of application like:

- Retail and logistics

- Ecommerce

- Medical and healthcare

- Advertising

- Knowledge management

Given multiple collections of entity representations like tables, files or text, the entity matching problem is defined as identifying all sets of entity representations that reference the same entity. Most studies in the domain of entity matching work under the assumption that the collections of entity entries on which the algorithm is applied have homogeneous structures and similar schemas. It is also often assumed that the matching identifies only the uniquely identifiable representations, ignoring the partial matches and similarity ranks. Thus, a broader problem definition was introduced under the name of Generalized Entity Matching.

The challenges of generalized entity matching in the Big Data context cover almost all the general challenges of big data solutions including dealing with data variety (heterogeneous data sources), velocity (the algorithms must be performant enough to process the data volume and provide the results at the required time by the use-case), and budget-aware processing (even if the data volume can be processed under the time restrictions, the compute-budget is usually a hard constraint for a solution to be profitable). In this post I will focus on understanding the most important challenges and aspects of deduplication and similarity search which are critical for developing an effective solution based on these methods.

Deduplication, in broad terms, deals with data that is already available or processed into a single data source and groups the data entries into sets that represent the same entity. A natural extension, which is usually part of the deduplication solution, is a merge and resolution algorithm that can reduce the groups of semantically equal entries into a new single entry. Deduplication is usually deployed as a background ad-hoc process in an enterprise with a goal to significantly improve the data quality. It is often part of a larger restructuring process, which can be followed by other services that ensure future data quality and prevent the need for deduplication in the future. These types of solutions are either developed internally or are provided by a B2B service.

Similarity search on the other hand can be seen as a subtask within a deduplication solution, finding the same or similar entries in a data source, given a query entry or a set of attributes. The application of similarity search is broader and can often be customer-facing (B2C) through features such as document search, recommender systems, and auto-completion in data entry systems.

Challenges and constraints

When designing an entity matching-based solution, we have to take into account different considerations and nuanced relations between the methodology used and the business impact. The main question that needs to be considered is: do we need the matches between entities to have 100% confidence or not (hard matches vs soft matches)? Just imagine the logistical hell if the result of deduplication leads to the merging of two unrelated products into a single entity or the legal consequences of merging two different people into a single entry.

In practice, the different scenarios usually follow one of two patterns:

- The solution is applied to the data relevant to the core business, so the matches need to be done with absolute certainty. As a consequence, we will find fewer matches because of the strict matching criteria.

→ There must be no false positives. Precision has to be 1. - The matches are not mission critical and are used in a recommender, auto-completion, search or similar system, both customer or internal facing. This allows for a more flexible definition of a match and we will find more matches overall.

→ Both precision and recall are maximized.

We will keep these two scenarios in mind when discussing the different methodologies.

Heterogeneity of data sources

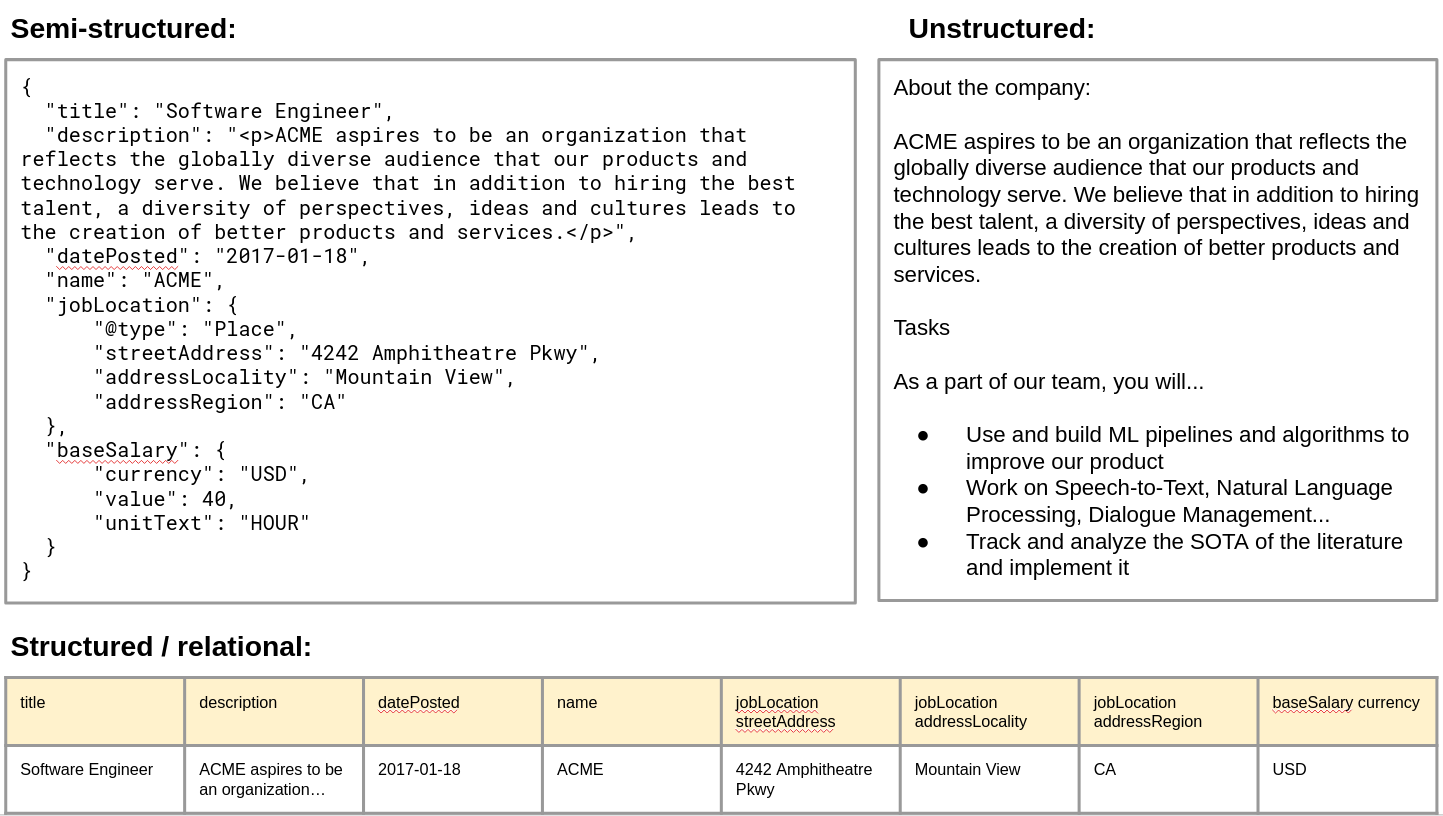

The datasets or the collections of entity entries can be represented in various data formats. We can categorize those as:

- Structured (tabular data, relational database)

- Semi-structured (XML, JSON, graph, tagged document)

- Unstructured (PDF, text, document)

When the data format is the same we can further differentiate if the collections have the same schema or not by categorizing them to:

- Homogeneous

- Heterogeneous

Independently of the data formats and schemas, the entries in collections can contain multiple data types:

- Text

- Boolean flags

- Enum - generalization of boolean

- List/set - generalization of many enum attributes

- Binary

- Graph

When developing an entity matching solution, the above properties of the specific datasets constrain the applicable methodologies we can use.

For example, if working with an unstructured dataset, we can exclude the attribute-based matching and blocking algorithms. However, if we are confident that a majority of data in the unstructured dataset reliably contains certain information, we can exploit that knowledge and extract that knowledge into attributes, and then apply the standard attribute-based matching.

Another example might be the case of working in a heterogeneous setting where we are matching semi-structured JSON data with a structured relational database. In this case, we can seek to flatten and normalize the JSON. If this is not possible we can use any of the matching and blocking methods applicable to semi-structured or unstructured datasets as we can always easily cast a more structured dataset to a less structured one.

Controlling the computational cost

During deduplication, the algorithm needs to consider all pairs of entries. It is obvious that a naive comparison of every pair of entities in the data would lead to the O(n²) run time. In the context of big data, such a solution is infeasible even on relatively small datasets. To overcome this limitation there exist many techniques such as efficient indexing, blocking or message passing techniques. These techniques reduce the search space and facilitate parallelization of entity matching algorithms and deployment on the distributed computing platforms which can significantly increase the efficiency and reduce time to solution.

Blocking is primarily used to prevent the unfeasible evaluation of the Cartesian product of all entities, but as a consequence, the reduced search space might also exclude some positive matches. Thus the question of reliability and other properties of the blocking index, such as pair completeness (recall), pair quality (precision), and reduction ratio, is important to consider within the specific problem context. Referencing back to the challenges and constraints section, let’s consider the two defined scenarios. In scenario 1, no false positives are tolerated due to implied business consequences. A lower recall and a number of false negatives can be tolerated to a degree. In scenario 2 however, a balance between precision and recall is desirable. Some minimum level of both precision and recall is needed (true positives should outnumber false positives and if possible false negatives) in order to have a useful result in the recommender system.

The most important factor to consider when choosing the blocking index is the cost-benefit trade-off. In the case of products, if we choose a high-level product category as the blocking index, the resulting blocks will be large, which leads to many unnecessary comparisons between entity pairs, which in turn leads to more computational cost and longer time to solutions. In contrast, if the blocking index is too specific, like product manufacturer and color, the resulting blocks might be too small and miss some true matches between entities that are grouped in different blocks due to bad data quality.

In an optimal case, we would already have a reliable blocking key (index) but these are mostly unavailable in heterogeneous datasets and are often unreliable with a single large homogenous data source (in the products-example above, the manufacturer attribute might have multiple different values with typos or other changes for the same manufacturer).

In cases where no existing attributes are available within entities that can be used as a blocking index, a synthetic (blocking) index can be computed. A variety of algorithms are available for computing the synthetic blocking index including Bigram Indexing, Sorted Neighborhood, and Canopy Clustering. The same cost-benefit trade-off applies to the synthetic blocking indexes, which are even more prone to sensitivity loss (losing the positive matches) when applied as a black box solution.

For more critical solutions, one often includes some domain knowledge about the data and attributes when computing the synthetic blocking index. For example, one might exploit unreliable partitioning keys (like product manufacturer) to increase the coverage confidence (by clustering manufacturer values and using cluster indices) while still significantly reducing the search space.

When dealing with data that lack useful metadata or attributes for blocking, one might have to compute the blocking index based on the content of entities. For this case, there is a possibility of using (deep learning) embeddings of data entries as the input to the clustering algorithm for producing a more reliable blocking index or finding the n-nearest-neighbors for comparison.

For even more demanding use cases like continuous entity matching, please refer to these two comprehensive reviews of all available state-of-the-art blocking methods.

After having the search space significantly reduced with blocking, it is still critical to exploit the possible parallelization of the matching process, especially in the case of deduplication or the partial pre-computation of similarities for similarity search. One consequence of parallel matching is that the result can contain overlapping groups, so an additional merging step needs to be introduced.

Further optimizations can be performed on the level of query picking (sampling strategy) during the iterative deduplication process, but are costly and highly dataset-specific.

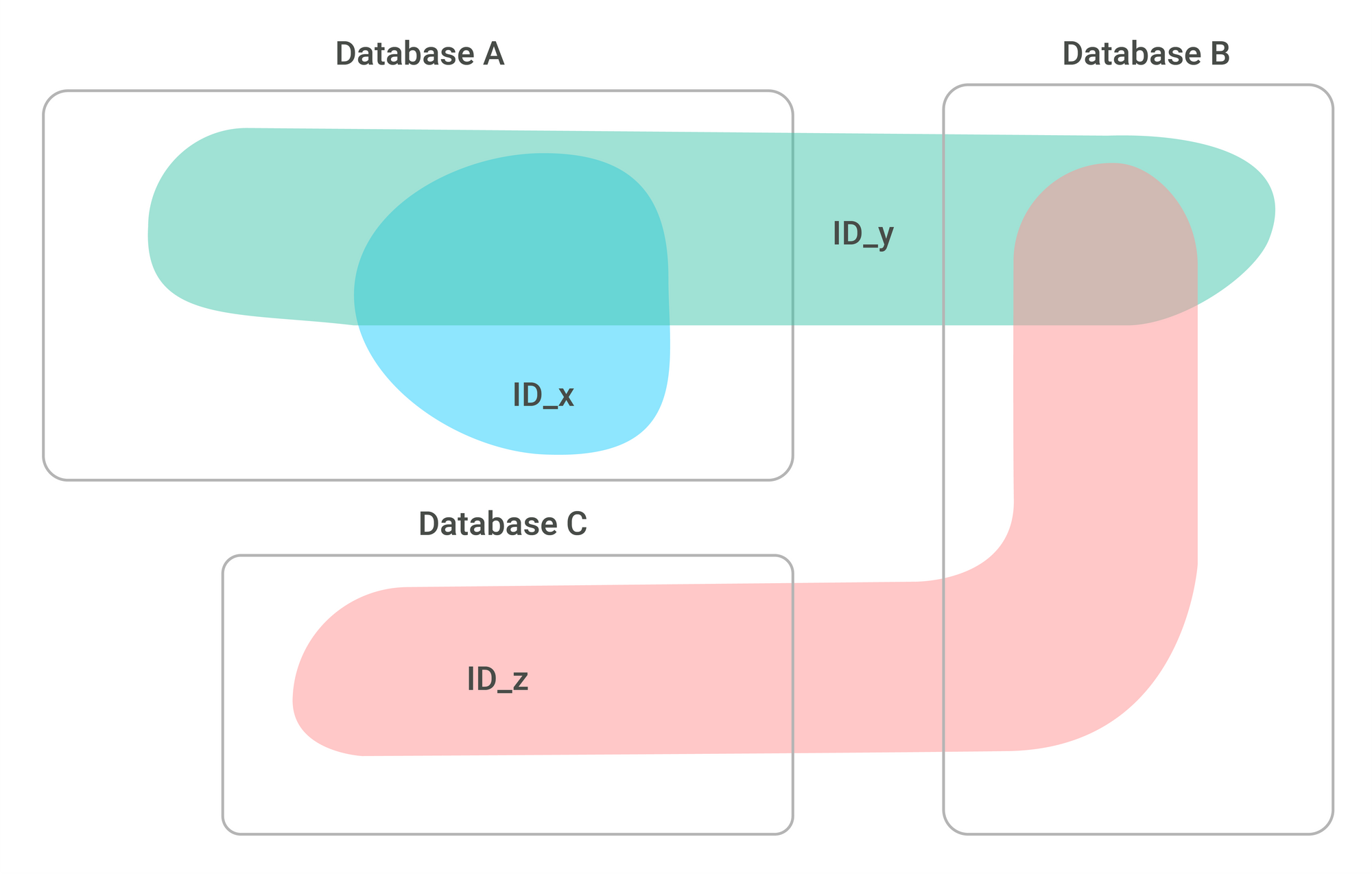

Identifier based matching

An identifier within a data source is an attribute which already matches identical entities. Every identifier is only valid on a certain scope, which typically does not cover all the available data (otherwise the problem would be already solved). It is often the case that during entity matching one has to exploit available identifiers which are incomplete, partially available, or span different scopes of the data. For example, if the dataset consists of multiple data sources, each data source can have its own unique identifiers. Some identifiers can have scopes that cover multiple data sources but only partially.

To exploit such overlapping partially-available identifiers, we can employ an iterative matching method to extend the scope of entity matching to the whole dataset. The main advantage of using available identifier is the 100% confidence in the matches as required for scenario 1 in the “Challenges and constraints” above (entity matching impacting the core business processes).

Partially-available identifiers can also be used as labels for training the classifiers of attribute-based or deep learning-based matching approaches.

Another very impactful methodology is using the identifiers (or attributes) as exclusion criteria. Those can be used in conjunction with matching criteria in the defined order of precedence to decide if the pair of representations is a true match. One can also take it a step further and integrate the exclusion criteria in the calculation of blocking index, where the search space can be reduced even further.

Attribute-based matching

Entities in structured datasets have a multitude of attributes, whose relevance for entity matching is not always clear. The similarity between individual attributes of different entities can be computed but takes on a different form depending on the data type. The following figure shows examples of the data types, their features and similarity metrics that can be computed on them.

| Data type | Feature | Similarity / Distance metric |

| Boolean | Boolean | Equality |

| Int | Int | Equality |

| Float | Float | Difference |

| Enum | Enum | Equality |

| Set (of enums or strings) | Set | Overlapping fraction |

| Geo-Coordinates | Geo-Coordinates | Euclidean distance

Tunnel distance Ellipsoidal-surface distance Road distance |

| String | Normalized String | Smith-Waterman Edit distance

Q-gram distance Jaro-Winkler distance Monge-Elkan distance Extended Jaccard coefficient SoftTFIDF similarity Longest Common Substring similarity Bag distance Compression distance Editex similarity Syllable Alignment distance |

| String | Vector Embedding | Euclidean distance

Cosine similarity Dot product |

After the similarity scores of all attributes between the two entities are computed, they need to be combined into a single similarity metric. This can be done in different ways, from domain knowledge-driven manual weighing of individual similarity scores to automated data-based methods that require a labeled dataset. For the later variant, any type of classifier model can be trained. Depending on the properties of the available dataset, one usually has to apply one of the following two approaches:

- Generating the dataset with manual labeling and active learning

- Exploiting the available unique identifiers as labels

Unique identifiers that are valid on a substantial subset of data are optimal to reuse for generating a labeled data set. If the scope of the unique identifier is too small, then the labeled dataset it produces might be too biased and not directly useful for training. This however can be used as a starting point for the active learning approach which is still better than starting from scratch.

If no partial identifiers are present that can be used as a labeled dataset, then the only available alternatives are the manual weighing of the similarity matrices. This is bound to produce suboptimal results but might be used as a baseline in cases there are no alternatives. The baseline can then be used as a starting point for active learning. Active learning methodology supports the manual labeling process to maximize the performance gains for every labeled sample (by picking the samples for labeling based on the highest uncertainty of the classifier model).

Independently of the dataset quality and the classifier confidence, with attribute matching, we can never be 100% confident in the matches as required for scenario 1 in the introduction. The only way to really use the attribute-based matching for scenario 1 is to have a manual validation step after the match generation. However, the uncertainty of the attribute-based matching is not an issue for scenario 2 where the output of the matching is only used as a recommendation generator in a business process or a customer experience.

Deep learning approaches

Despite the ongoing research since 1946 in different aspects and domains of entity matching, the problem is still open and does not have a satisfactory solution. The requirements of intensive human involvement in feature engineering, tuning, manual labeling, and integrating domain knowledge into the entity matching solution largely remain. With the advances in deep learning, novel methods enable approaching the entity matching problem from a different perspective and potentially increasing the performance and reducing the need for human involvement in the development process.

Promising deep learning concepts that enable a different type of entity matching are word and document encoders. These neural networks are trained to produce embeddings in latent space whose distance should be proportional to the similarity of the entities in the target domain. Such neural-network-based encoders come in different varieties and are suited for several domains. For example, using the distributed word representations with RNNs and LSTMs, the authors of DeepER were able to develop a novel entity matching system with high accuracy and efficiency that requires less human effort. An overview of deep learning-based entity matching approaches can be found here.

While the above methods improved multiple aspects of entity matching and set the new state-of-the-art benchmark on datasets, they still rely on having available large and good-quality labeled datasets which are mostly not available in a real-world setting. Thus, novel deep learning approaches have been developed to specifically tackle the low resource settings. For example, an architecture combining transfer learning and active learning, dubbed Deep Transfer Active Learning, was developed and exploits the publicly available datasets to train a high-resource model and transfer-learn to a low-resource target setting with very efficient active learning labeling, minimizing the human effort while still retaining the high performance. Another innovative deep learning approach is the Ditto architecture which enables direct entity matching on datasets with heterogeneous schemas.

Methods that can completely overcome the need for labeled datasets are self-supervised learning approaches, like CollaborER and KRISS, which achieve state-of-the-art entity matching performance and can even outperform some supervised-learning-based methods.

In the follow-up post, I will cover more advanced techniques and architectures in entity matching including federated entity resolution and real-time data entity matching.